Thursday, December 8, 2016

12/6/16

$3415. Three thousand, four hundred and fifteen dollars-- all raised through the efforts of a good community that I couldn't be more grateful for having. Whether family, friends, acquaintances, or friends of friends, they all took part in supporting our mission by donating. I was very surprised to see us break 20% of our goal. It's been a great and productive three weeks, but fundraising has slowed down; I might send a few more emails, but I believe that this is the majority of the money we'll be able to raise. The next step will be making our way to a series, and we already have one almost through production. This video will explore TAVR a bit more. We might come to the plan of covering only a few diseases, tantamount to (or possibly lower-prioritized than) discussing the surgeries related to them. Surgeries, the operations being performed, are what's important to people-- not general knowledge of information that isn't relevant to them. I'm interested to see how this will evolve; we want to eventually get some more serious investors involved in our idea, or allow it to expand beyond us, but only time will tell.

Friday, November 18, 2016

November Update/ Heartwell Project Fundraiser Launch

The Heartwell Project's fundraiser has now been active and circulating around social media (and in the email inboxes of a few dozen friends) for more than a full day. We've already raised more than $700! It feels great to finally get things moving; a lot of my internship-related work has been subverted in the past few weeks due to school, college apps and other priorities, and this was one thing that I knew I just had to get started on. The fall has sped by-- its already been five months since Understanding Aortic Stenosis was posted to YouTube. I see no better way to end the year than by raising money for the next chapter of this project, and I'm glad things are going swimmingly.

However, before talking more about Heartwell, let's discuss the state of the internship as a whole.

To be completely honest, I don't have much more to say about most of Dr. Nguyen's cases-- he doesn't perform specific ones for his pleasure, he does them because it's a part of his job and he is specialized in a handful of procedures. This limits the kinds of surgery that I get to see, and I feel as though I've covered most of what he does frequently--TAVRs/TAVIs, CABGs, AVRs, MVRs...I've talked about them all, and extensively so. If I were to go any further, it would be into the realm of serious and verging-on-professional-tier research information; the point of this blog was never to do that, but rather to break down cases so that more people could understand them. It's basically just a more in-depth (albeit written) form of The Heartwell Project, and it was through this blog that I first learned to understand medical information. For my first few posts to the blog, I was learning alongside all those who read it. It's meant a lot to me in the past year, but these case analyses will be fewer in number over the coming months, unless I feel that they're merited.

I'll be keeping the blog primarily focused on project updates for the foreseeable future; provided that we raise the requisite amount of money to carry on into the production of the video series, the blog will then segue into covering that progression. I'm excited to see how things will develop!

Here's a link to the fundraiser, which I encourage any readers to take a look at and consider donating to:

https://www.crowdrise.com/the-heartwell-project

To be completely honest, I don't have much more to say about most of Dr. Nguyen's cases-- he doesn't perform specific ones for his pleasure, he does them because it's a part of his job and he is specialized in a handful of procedures. This limits the kinds of surgery that I get to see, and I feel as though I've covered most of what he does frequently--TAVRs/TAVIs, CABGs, AVRs, MVRs...I've talked about them all, and extensively so. If I were to go any further, it would be into the realm of serious and verging-on-professional-tier research information; the point of this blog was never to do that, but rather to break down cases so that more people could understand them. It's basically just a more in-depth (albeit written) form of The Heartwell Project, and it was through this blog that I first learned to understand medical information. For my first few posts to the blog, I was learning alongside all those who read it. It's meant a lot to me in the past year, but these case analyses will be fewer in number over the coming months, unless I feel that they're merited.

I'll be keeping the blog primarily focused on project updates for the foreseeable future; provided that we raise the requisite amount of money to carry on into the production of the video series, the blog will then segue into covering that progression. I'm excited to see how things will develop!

Here's a link to the fundraiser, which I encourage any readers to take a look at and consider donating to:

https://www.crowdrise.com/the-heartwell-project

Wednesday, October 26, 2016

10/19/16

Things have been very busy recently, and it's now more difficult for me to make time to craft lengthy, in-depth weekly posts, or get the OR time to put them together at all. This is a departure from eight or so months of (what I'd call, at least) consistent content, and I hate to be abandoning that. I'll be moving to a bi-monthly schedule proceeding into the winter--save for special announcements and things of that nature. However, there's no shortage of posts on this blog, so if you're new here, feel free to browse around!

Today's case was a redo mitral valve replacement. I'm not sure about the context, or why Dr. Nguyen decided to repeat the procedure, but the patient's condition must have been concerning enough to merit it. Having never seen a redo before, this case was interesting-- the fallout from the previous surgery was very visible. Still-recovering myocardial tissue showed blackened marks from the last case's cautery burns. I arrived before bypass, and progress was still being made to expose the aorta for the start of that procedure. I did a general overview of mitral replacements last post, so I thought it'd be fun to get into the true details of the surgery-- for example, bypass prep (e.g., cardioplegia use). To start on that, Dr. Nguyen usually uses retrograde cardioplegia instead of antegrade-- the difference being cannulation through the right-atrium-feeding coronary sinus, instead of the aortic root's coronary artery. Today was no outlier, and he went retrograde; this was done in hopes of maintaining certain heart conditions proceeding into the replacement. Retrograde delivery arrests the heart more slowly, and generally, antegrade is only safe for all patients (especially those suffering from aortic regurgitation) if administrated in tandem with retrograde. Myocardial damage can occur if it is used alone.

After bypass is wrapped up, the tissue surrounding the heart is held open with lengths of suture thread, pressed against the chest cavity, to make room to maneuver about the myocardium and secure an opening for the pump(s). Saline sprays and a vacuum are used to facilitate the removal of blood, and ensure a clear attachment from the pump to the opening.The draw pump tube, situated at the inferior vena cava's opening into the right atrium, is noticeably wider in diameter than the push pump at the aortic arch; I'm not sure why this is. I found a lot of good information about the more detail-heavy aspects of bypass on this website, so definitely take a look at that. It probably does a better overview of it than I have over the course of my many posts, and is all in one place to boot:

Today's case was a redo mitral valve replacement. I'm not sure about the context, or why Dr. Nguyen decided to repeat the procedure, but the patient's condition must have been concerning enough to merit it. Having never seen a redo before, this case was interesting-- the fallout from the previous surgery was very visible. Still-recovering myocardial tissue showed blackened marks from the last case's cautery burns. I arrived before bypass, and progress was still being made to expose the aorta for the start of that procedure. I did a general overview of mitral replacements last post, so I thought it'd be fun to get into the true details of the surgery-- for example, bypass prep (e.g., cardioplegia use). To start on that, Dr. Nguyen usually uses retrograde cardioplegia instead of antegrade-- the difference being cannulation through the right-atrium-feeding coronary sinus, instead of the aortic root's coronary artery. Today was no outlier, and he went retrograde; this was done in hopes of maintaining certain heart conditions proceeding into the replacement. Retrograde delivery arrests the heart more slowly, and generally, antegrade is only safe for all patients (especially those suffering from aortic regurgitation) if administrated in tandem with retrograde. Myocardial damage can occur if it is used alone.

After bypass is wrapped up, the tissue surrounding the heart is held open with lengths of suture thread, pressed against the chest cavity, to make room to maneuver about the myocardium and secure an opening for the pump(s). Saline sprays and a vacuum are used to facilitate the removal of blood, and ensure a clear attachment from the pump to the opening.The draw pump tube, situated at the inferior vena cava's opening into the right atrium, is noticeably wider in diameter than the push pump at the aortic arch; I'm not sure why this is. I found a lot of good information about the more detail-heavy aspects of bypass on this website, so definitely take a look at that. It probably does a better overview of it than I have over the course of my many posts, and is all in one place to boot:

Jumping further into the case, the mitral entrance Dr. Nguyen picked was...interesting. Three scoop-like metal supports, ringing the chest retractor and extending into the sternal incision, were used to hold the heart up and rotate it to the left in its cavity. This provides a very narrow pathway from under the right side of the heart to the mitral valve, and it's probably the most difficult-looking task I've seen in the OR (yet). Standard tools can't be used to remove the valve, simply because of how deep down it is-- the task calls for specialized elongated cutting instruments.

The next phase of the Heartwell Project is set up and ready to go, though I'm a bit tired of giving "soon, guys!" updates about it. Early November is our target launch window, and has been for a few weeks now. I might not talk about it until then.

The next phase of the Heartwell Project is set up and ready to go, though I'm a bit tired of giving "soon, guys!" updates about it. Early November is our target launch window, and has been for a few weeks now. I might not talk about it until then.

Monday, October 10, 2016

9/28/16

Despite being quite a standard day at the HVI, I got to see (a part of) a case that I haven't seen in a while-- an open-heart mitral valve replacement. A mitral replacement is performed to counter calcification or other interruptions to blood flow in the mitral valve, and replaces the defective valve with a prosthetic or biological one. This is a fun surgery to watch, as its procedure doesn't leave much to the imagination. First, the sternum is split with a saw in an incision 3-4 inches in length, and underlying tissues are then bisected length-wise to get a decent view of the heart. Cardioplegia is administered to slow the heart and prepare for bypass. The cardiopulmonary bypass machine is used to pump blood throughout the body in place of the heart, and reoxygenate it without the use of the lungs; it does this by cannulating the vena cava or right atrium to draw out deoxygenated blood, oxygenating it outside of the body, and then feeding it back into the ascending aorta. This allows for the attending surgeons to operate on a still heart and chest, which is pretty useful. Going further, an incision is made in the heart's left atrium, exposing the mitral valve. After removing the diseased valve leaflets and annular tissue, there is a long preparation for the new valve's insertion into the mitral space. I like to call it "scaffolding": a ring of sutures is sewn into the tissue, and then used to lower in the replacement valve. I'll include a picture of this (a).

Arriving at the tail end of the surgery, I missed all of this, and saw more of the cleanup process than anything else. The patient soon finished being weaned off of the bypass machine, and the final sutures were performed in the chest cavity. Shortly after, chest tubes were inserted into the mediastinal cavity to help with post-op fluid drainage. In the days following an invasive surgical procedure, a mixture of body fluids will leak from the damage done to the tissue inside the chest-- the chest tubes provide a place for that fluid to drain to, preventing against nasty infections and other complications. Valuable, but a bit gross nonetheless. One might also wonder how the sternum is pieced back together after being sawed in half, which yields a more complicated answer than one would expect. Well, metal wires are looped through the tissues directly adjacent to the center of the sternum, then cut before another loop is made. This results in multiple horizontal lines of wire, running under both sides of the sternum and out through the left and right breast.These lines are then crossed and twisted until the two pieces of the sternum meet. After this, the excess pieces are clipped, and the performing surgeon tightens the twisted wires as they see fit. The wire-ties are then pressed down and into the surrounding tissue. It's almost like heavy duty suturing, but is a bit hard to explain without a picture-- see below (b). A standard sealing/suture procedure reattaches the tissue above the sternal plate back together, ending the surgery.

Arriving at the tail end of the surgery, I missed all of this, and saw more of the cleanup process than anything else. The patient soon finished being weaned off of the bypass machine, and the final sutures were performed in the chest cavity. Shortly after, chest tubes were inserted into the mediastinal cavity to help with post-op fluid drainage. In the days following an invasive surgical procedure, a mixture of body fluids will leak from the damage done to the tissue inside the chest-- the chest tubes provide a place for that fluid to drain to, preventing against nasty infections and other complications. Valuable, but a bit gross nonetheless. One might also wonder how the sternum is pieced back together after being sawed in half, which yields a more complicated answer than one would expect. Well, metal wires are looped through the tissues directly adjacent to the center of the sternum, then cut before another loop is made. This results in multiple horizontal lines of wire, running under both sides of the sternum and out through the left and right breast.These lines are then crossed and twisted until the two pieces of the sternum meet. After this, the excess pieces are clipped, and the performing surgeon tightens the twisted wires as they see fit. The wire-ties are then pressed down and into the surrounding tissue. It's almost like heavy duty suturing, but is a bit hard to explain without a picture-- see below (b). A standard sealing/suture procedure reattaches the tissue above the sternal plate back together, ending the surgery.

Ex. A.

Wednesday, September 21, 2016

9/19/16

This afternoon, I met up with Dr. Nguyen a bit serendipitously- we both happened to be walking over the skybridge between Memorial Hermann's main building and the HVI at the same time, and joined up there. It'd been a few weeks since we'd talked in person, which made catching up more interesting than usual. Extending past my conversations with Tom, there was an unusual air of excitement at Memorial Hermann today; it's an unforgettable place that has had a huge impact on the past year of my life, and just a month away from it had fuzzed my memory. The hallways of 2850, the panoramic view of Rice/downtown Houston, the OR and the smell of the cautery (not a positive memory)....all of it had a newness to it that I haven't felt in a while. It's so, so good to be back.

After a bit of small talk and brainstorming in Dr. Nguyen's office, we went quiet and did some work. Shortly after, we went to a post-op patient checkup down the hall. He was a MIVR (minimally-invasive valve replacement) recipient, likely in his late 60s/early 70s. With most of the incisions sealed and healing, Dr. Nguyen discussed comfort options for the patient more than anything- remedying small issues, making sure the former patient could get back on his feet (not literally, though, because he was already walking). The man had been prescribed plavix, a standard blood thinner, along with Tylenol 3/codeine phosphate, potassium pills, and a few other medications. He reported being somewhat uncomfortable as a result of the codeine, but was recovering well aside from that. Dr. Nguyen was still waiting for some lab tests to return, but offered to cease most of the treatments if the labs reported a clean bill of cardiovascular health. It’s always nice to see quick patient recoveries.

At around 2:00pm, I joined Dr. Nguyen on the 7th floor of the HVI for a double CABG. We arrived fairly far into prep, as the saphenous vein harvest and sternotomy were thoroughly underway. CABG procedure is something I’ve covered time and time again, so if anyone needs a refresher, here’s a good reference post:

https://www.blogger.com/blogger.g?blogID=8533419574158229049#editor/target=post;postID=7620191396548475921;onPublishedMenu=allposts;onClosedMenu=allposts;postNum=9;src=link

Continuing on, the saph vein harvest went a bit poorly, which was really no fault of the surgeons. The vein was fragile and almost breaking apart, making it difficult to get a significant length for the graft. They salvaged as much as possible, and it began to go a bit better as they spotted some possible alternatives. Dr. Nguyen set to work on the interior mammary harvest, using the cautery to carve away at bits of tissue lining the artery. I wasn’t able to see any of the surgery past this point, and unfortunately had to head out. If you're new to the blog, I'll be posting more complete surgeries in the future, and hopefully diversifying a bit; CABGs are fun to see, but I might branch off to shadow some other surgeons- getting back into the swing of things with a few new twists, I suppose. More to come soon!

P.S., we’ve got some Heartwell Project updates just around the corner.

Wednesday, August 24, 2016

8/18/16

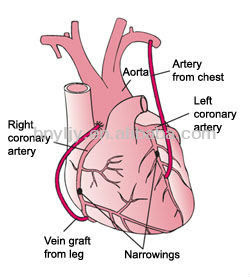

Today was a triple bypass CABG- nothing too out of the ordinary, but still a fun surgery to watch. I still want to see a VSARR (valve-sparing aortic root replacement), but those don’t seem to happen too often, which is a bummer. Digressions aside, before the case started, other surgeons called Dr. Nguyen to inform him of stenosis in the superior vena cava, one of the two venous pathways to the heart. It was a potential risk, but it must not have been serious enough, as they opted to continue. Most of what I saw was standard for CABGs; saphenous vein gets harvested from the left leg, the interior mammary artery gets one end detached, and both parts get grafted onto the coronary artery bed. The triple bypass, however, introduces an interesting twist on this familiar procedure- the saphenous vein is actually split in two for the arterial bypass. Instead of just linking the aortic arch to one artery, the saphenous vein bifurcates and leads to two spots on the heart. This is why the initial saphenous vein harvest is so long. It is divided into two parts, with each segment leading to different blockages in the coronary artery bed. This is all sorta complicated, so here’s a picture to explain it a bit better:

The saphenous vein, in its two parts, are the two white pieces on the right of the heart.Triple bypasses seem to take much longer than the doubles I'm used to seeing; the third piece of the graft takes some extra work to prepare for. But, I’m not sure how extensive the saphenous vein’s cleaning process is (wish I had seen it!).

I'll probably have some new stuff coming out soon about the Heartwell Project soon. School has just started, and I have a beginning-of-year retreat going on next week- so, I'll really just have to play it by ear until things get back to normal. I'm not sure how my time in the OR will fit into my new schedule, but my fingers are crossed for any morning but Friday (that's valve clinic/patient rounds, which just isn't as fun). Thanks for reading!

Sunday, August 14, 2016

8/4/16

Last Thursday, I finally returned to the idea of doing live presentations of the Understanding Aortic Stenosis video. In the weeks prior to this, I had been in contact with the event coordinators at The Forum at Memorial Woods, working out a good date to present. We eventually decided that it could be done in tandem with a lunch/dessert event- the seniors got to come for food as well as a health presentation, which is a bit more enticing. I was really excited about this event, and it couldn't have gone any better; all of the audio and video aspects of the presentation worked beautifully. The seniors had a great deal of questions, mostly regarding operations they or their family members had in the past. Some I had to politely dismiss, on the grounds that I'm not a doctor and can't diagnose heart diseases. I still had a great time fielding questions, though, and am looking forward to doing more of these presentations this fall.

Wednesday, August 3, 2016

7/28/16

Today was my first day back in the OR, and I picked a good morning to come. All the while, I had company in some interns from UT, and got to chat with Dr. Nguyen for a bit before he scrubbed in. It's interesting to see how calm and collected these surgeons can be before cutting someone open, but I suppose a lot of the pre-op excitement dies down when you're performing multiple operations each day. One great thing about today was that one of the performing doctors decided to use a headcam, which is perfect for giving us lowly students some insight into the surgery; a fiberoptic cable links whatever they're seeing to suspended TV screens around the room, displaying footage in real time. Otherwise, the only good view in the house is from the anesthesiologist's corner of the room, which can get a bit crowded. Today's case was a double bypass, and was pretty standard fare- sternotomy, saphenous vein harvest from the left leg, interior mammary harvest from the left breast, etc. At this point, unless I see a new procedure or surgical method, I can sit back and enjoy the surgeons' work instead of tapping away at my phone taking notes. But, I did find out about one thing: why the saphenous vein harvests are done endoscopically (within the leg), instead of making an incision along the length of the leg and opening it up completely. When I wrote about the first surgery in which I saw a vein harvest, I didnt know what it was (formally) called, and looked it up to find out. Most of the picture results displayed a long incision spanning the length of the leg, which seemed ridiculously excessive. Turns out that the latter method is is much more traumatic, and takes much longer to recover from. Here's a picture of endoscopic vs. standard vein harvest techniques below, to give an idea of what I'm talking about:

I also watched one of the doctors prep the saphenous vein for the graft, which is something I've never really paid attention to. The vein gets flushed of blood, the leads going to the venules (smaller vessels along the vein) are sutured shut, and the vein segment is dyed purple to distinguish it as foreign tissue when the time comes to graft it onto the myocardium.

I also watched one of the doctors prep the saphenous vein for the graft, which is something I've never really paid attention to. The vein gets flushed of blood, the leads going to the venules (smaller vessels along the vein) are sutured shut, and the vein segment is dyed purple to distinguish it as foreign tissue when the time comes to graft it onto the myocardium.

Wednesday, July 27, 2016

Update 7/26/16: I'm back (plus Heartwell info)!

Wow, it's already been three weeks since I gave my "I'm leaving" announcement. I'm really getting tired of the word hiatus, or any of its synonyms, so I'm going to go after things a bit more aggressively in the next two weeks before I have to use it again- I was thinking two blog posts a week, which is what I should've been doing since the beginning of the summer, but hey- Junior year was hard (can I still get away with that excuse?). Joking aside, with the exception of the past ~21 days, I'm really happy that I've been able to keep up the momentum of The Heartwell Project. "Understanding Aortic Stenosis" almost has 20,000 views on Youtube, something I definitely didn't expect to ever happen. People have learned from something I've created, and I really can't say enough about how awesome that feels. The TV appearance only stoked the forge there, and made our goal seem even more tangible; I'd like to keep that going. I'm currently laying out some plans to continue the project, which basically hinges on one thing: how much money we'll be able to put into it. So, I'll reach out, see what's available, try to organize some fundraising events, and see where things go. Maybe even set out a timeline for different videos and topics- which I'll consult Dr. Nguyen for- and get an idea of which diseases are most worth attending to. This is more than a high school student's "hey, look at me!" project for colleges, it's an extremely potent educational tool. And I want to see it through. More to come soon, in regards to The Heartwell Project and my experiences in the OR.

Monday, July 4, 2016

7/1/16

Back again with a double-header blog post: an HVI visit and a (rather unexpected) talking segment on TV. I made it on Good Day Houston in the end, and got to talk a bit about my involvement with the Heartwell Project. Besides those two things, I wanted to inform everyone that this blog might be dormant for the next two weeks- I'm on vacation and visiting with family in South Carolina. I might do an update for something, but it probably won't be as meaty as what I've been putting out in the past few months. I expect to return to a regular blog schedule around the week of the 24th- I'll try to make it something special! But, without further ado...

Valve conference was fairly standard today, except for a few critical AS cases- those patients had multiple stenosed valves, showing themselves to be presumptive wildcards for the OR teams. The comorbidities (additional factors that increase the risk of surgery failure or death) were easy to pick out for these patients, and as a result, almost all of the recommended procedure options were minimally invasive. Many were TAVRs, simply because that procedure would solve the first of many problems that needed to be addressed for these people. Did I ever mention that the aorta is the largest blood vessel in the human body? Well, it's pretty important that this super-artery (and its accompanying valve) stay functioning correctly. Healthy blood outflow is always nice to have.

Two commercial MitraClip candidates were discussed near the tail end of the conference- one with mild aortic sclerosis, mild tricuspid regurgitation, and moderate/high mitral regurgitation; the other another with severe mitral regurgitation, mild tricuspid regurgitation, aortic regurgitation, prolapsed anterior and posterior leaflets and a few other issues. As these patients were fairly high-risk, they were definite candidates for the MitraClip procedure, which stands as the only percutaneous (non-surgical) way to repair the mitral valve. It's pretty neat. A part of the discussion hinged around the decision of how to approach the second Mitraclip patient- the choice between transeptal and transapical entry points. Judging from the CR scan, both approaches were viable, but there were other things that weighed on the doctors' decisions. If the transeptal approach was chosen, it would be the first procedure of its kind, utilizing a new kind of catheter delivery system. It has only been tested on pigs so far, and because of that, some doctors were cautious about using it and wanted one or two successful cases to be available for reference. The patient's roomy left atrium would make the transapical catheter's entry easier, but Dr Nguyen voted transseptal- saying, 'we need to start [using the transeptal approach] sometime.' Transeptal was chosen in the end.

So, remember when I said I wouldn't be going on TV, and was relegated to an audience position with Matt? Well, that was true. But we got to do a lot more than we expected with said audience positions. When I arrived, Dr. Nguyen was still a few minutes from going on, and we had time to get comfortable; but, just as I was settling in and making small talk, a woman approached us- clip-on microphones in hand- and asked us to put them on. We did, and sat to watch Deborah Duncan's exchange with Dr. Nguyen on the stage in front of us. Soon enough, the topic of conversation turned to patient education, providing Matt and I with quite a foothold in the discussion. We both got to speak about what we had done for the project and how it had impacted us, and it became a really valuable experience. We were no longer just spectators, but a real part of the show. They also recruited me to do an Australian accent as part of another segment, which I'm glad none of my friends saw. Being on TV is a blast.

I hope everyone had a happy 4th of July!

Thursday, June 23, 2016

6/20/16

Last week, some scheduling conflicts arose and Dr. Nguyen was out of town for a few days. making me unable to go to MH. I also had to reschedule a presentation of the Understanding Aortic Stenosis video at The Gardens of Bellaire, a senior community here in Houston. That's pushed it awfully close to another presentation I'm doing at the Elmcroft senior community, but I'll be able to do both. I'm interested in seeing how much the seniors will contribute to the discussion; many of them just want to get to bingo. I'll see how the presentations go and report the details here. Anyways, here's the case from June 20th.

Today was a single CABG (coronary artery bypass graft), a procedure that I haven't exactly seen yet. It's really just half of a double CABG, if that makes sense, since only one new vessel is being grafted on. So, in this case, only the saphenous vein got taken, while the interior mammary artery (which gets used in a double CABG) is disregarded. I forgot to mention (last time I talked about CABG) that the saphenous vein grafts that I've seen have all been harvested endoscopically, meaning that a probe was inserted into the leg to extract them. I recently learned that there is an "open" method that requires the leg to be cut open length-wise, giving a clear view at the tissue and veins. Today's endoscopic vein harvest could've gone better, as some problems arose with getting appropriate vein segment lengths- I'm not sure if this was a technical issue, but I'd really like to see if the open method is any easier. This seemingly simple misstep made the surgery much longer than expected, delaying bypass and all of the "interesting" parts of the surgery. Nonetheless, the graft placement went rather well, and was definitely the highlight of the case. Grafting the saphenous vein onto the coronary arteries is a lot more complicated than dealing wth the interior mammary artery. With the saphenous, both ends are being attached to the heart, rather than just one with the interior mammary. Interesting instruments are brought in to support the graft placement- my favorite is this gray-colored device with two prongs that encircles the graft area. It has two sets of gears that seem to be used to tighten or loosen the grip on the myocardium, and is really cool to see in action. I still don't know what it is called, though, and "gray rotator tool for CABG" yielded no results on google images. I'll keep looking.

I’ll have plenty of interesting stuff to report about early next week, including the Elmcroft visit and (possibly) another case. I recently learned that the producers of Great Day Houston won't be able to fit Matt and I onto their TV spot on the 27th, but Dr. Nguyen will still be on that morning to talk about our project. It won't be as cool without us, but hey, things happen. I definitely recommend that you all tune in and see what he says about it!

Wednesday, June 8, 2016

6/8/16

After a great weekend at Free Press Summerfest, a music festival here in Houston, I return with the memorable events of last week- pertaining to the HVI and Heartwell, of course. Last Wednesday, I entered some previously uncharted territory by staying for an entire case. It was a double coronary artery bypass (CABG) via sternotomy, and a great surgery to watch. I've mentioned in earlier blog posts that the more invasive the procedure, the easier it is to see what's going on; here, I could see everything, especially when the anesthesiologist wasn't tending to the patient's anticoagulant needs. From that angle, I could peer down at the chest cavity, able to see the performing doctors' precise techniques as they worked to graft the new arteries to the patient's heart. Reflections aside, I'll explain the procedure in brief (brief, only because I have some other things to discuss in this post). Coronary artery bypasses allow the coronary arteries to receive proper blood flow if their normal vessels are blocked by plaque, which is usually a result of high cholesterol. Rather than doing something like an angioplasty to repair existing vessels, a CABG uses grafts from other vessels in the body. For this double bypass, a saphenous vein segment was taken from the patient's left leg, and one end of the left interior mammary artery. One might ask, "why one end?" That is because the other is already connected to the subclavian artery, which receives a healthy blood flow from the aorta. Detaching it completely would be super unnecessary, as another hole would have to be created for the other end of the mammary artery. So, the saphenous vein graft connects from the aorta to some part of the right coronary artery, and the interior mammary artery connects from the subclavian artery to some part of the left coronary artery. It was very difficult to tell which of the tiny coronary vessels the new artery and vein were being sutured onto, in this specific case, so that's about as precise as I can be. I will link a picture at the bottom, though those vessel connections might not have been the same as the ones in this case. It all depends on what coronary segments are blocked.

What I really wanted to discuss in this post was my first presentation of the Understanding Aortic Stenosis video. I went to the Amelia Parc senior community, where my grandmother lives, to present the video and do a short Q&A about it. The elderly people there were really receptive of the video, and some had a lot to say about it- ranging from questions to personal accounts of dealing with heart disease. It was good to get the video out to our target audience, as they're the ones who we want to be getting across to. They're the ones meeting with doctors about disease treatment and trying to decipher things. The secret to a good senior community presentation, I've learned, is to stay far away from bingo time; as soon as that started, a good part of the group I had gathered rushed out. I'd never seen people that old move so quickly.

By the way, I might do more local senior community visits- in fact, I already have two set up for this month. If you guys have any suggestions for places to visit and present this information, feel free to contact me or comment on the post. Thanks!

Double CABG (general overview):

What I really wanted to discuss in this post was my first presentation of the Understanding Aortic Stenosis video. I went to the Amelia Parc senior community, where my grandmother lives, to present the video and do a short Q&A about it. The elderly people there were really receptive of the video, and some had a lot to say about it- ranging from questions to personal accounts of dealing with heart disease. It was good to get the video out to our target audience, as they're the ones who we want to be getting across to. They're the ones meeting with doctors about disease treatment and trying to decipher things. The secret to a good senior community presentation, I've learned, is to stay far away from bingo time; as soon as that started, a good part of the group I had gathered rushed out. I'd never seen people that old move so quickly.

By the way, I might do more local senior community visits- in fact, I already have two set up for this month. If you guys have any suggestions for places to visit and present this information, feel free to contact me or comment on the post. Thanks!

Double CABG (general overview):

Sunday, May 29, 2016

5/29/16

Last week, we posted a complete video to our YouTube channel called Understanding Aortic Stenosis. This was a big moment for our team, and we wanted to spread it around as quickly as possible- as of today, the video has accumulated over 700 views. I'd say we accomplished that goal. The video's success marked the first major stride towards developing the Heartwell Project, our effort towards educating everyday people of all backgrounds about heart disease. As I've said in previous posts, this summer is not meant to be a dormant period for it, so we'll continue to make progress. We also have a TV appearance with Deborah Duncan coming up at the end of June, which will work wonders in regards to our publicity. I see a lot of good things in The Heartwell Project, an incredible amount of potential that we're only starting to tap into. In addition to all of this, I have arranged to present the video (and do a Q&A) in an elderly community in Dallas next weekend. I'm so excited to host this whole process on my internship blog- it really tells a story of my thoughts and experiences throughout The Heartwell Project's development. Despite the huge importance I've been putting on the project, I haven't forgotten my "roots" at the HVI. I'll be able to join Dr. Nguyen for more surgeries, and school can't get in the way. Summer 2016 is going to be eventful, try to keep up!

Here's a link to our channel:

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC600D_nPsIPZvv8zBbyjSqw

Monday, May 16, 2016

5/13/16

This morning's events were almost identical to last week's, with the exception being a rather interesting lecture that I attended before valve conference. The lecture was about robot-assisted tumor removals in the mediastinum (the upper chest cavity, containing the heart and lungs and surrounded by the ribs), something I'd never learned about. What really interested me about this lecture was the footage the doctors had of the surgery. The robotic arms sent into the mediastinum were accompanied by a high-quality video camera, which gave everyone watching the lecture a really great look at the cavity and the movement of the robotic arms. Robot-assisted surgery is being heralded as the next big step for minimally invasive surgery, and many of the doctors at the lecture were genuinely impressed by the robot's range of movement. The two robotic arms are even equipped with cauteries, special tools that use an electric current to burn through tissue. After the lecture, the room broke out into (well-mediated) discussion, with the doctors speaking their minds about the footage- some argued that the dexterity of a human hand would be hard to match using a machine, while others preferred the robot assistance for its cleanliness and quicker patient recovery time. The latter argument became much stronger after the lecturer told everyone that the patient from the footage went home just one day after the surgery. A thoracotomy tumor removal would take weeks to heal, and leave the patient with a noticeable scar along his or her chest; a robot-assisted removal, however, just leaves three small puncture holes. The world of thoracic surgery is truly changing rapidly.

Here's a video example of a robot-assisted posterior mediastinal tumor removal. This might be graphic for some:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=arUrgtTv1TY

P.S, I've had a bit of a cold recently, which is why this post is going up so late- but hey, better late than never.

Here's a video example of a robot-assisted posterior mediastinal tumor removal. This might be graphic for some:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=arUrgtTv1TY

P.S, I've had a bit of a cold recently, which is why this post is going up so late- but hey, better late than never.

Monday, May 9, 2016

5/6/16

Notice anything different around here? Though I'm sure some of you were super attached to the old gray color on this blog, I wasn't a huge fan- so, I changed the template and colors. I write on this blog almost weekly, so I see it frequently enough to want a design I'm actually happy with. I think this new one is an improvement.

Today, as I suspected, Dr. Nguyen did not have any cases. Despite this, it was still a great morning; after getting coffee and a banana, I met with Dr. Nguyen at valve conference in the HVI. It has been at least three weeks since I have attended a conference, and today's visit represented a healthy return to the lively, doctor-filled room. I got there early enough to get an agenda hand-out from one of the doctors mediating the conference, which covered the patient names and the doctors responsible for their cases. It became way easier to soak up and understand what they were referencing in conversation, as the patients' conditions were on the pages. After finishing patient rounds, Dr. Nguyen, his assistant Loren and I went down to imaging to see one of his patient's 3D TTEs (3D transthoracic echocardiographs). These are very different from echocardiograms, which are what most people imagine when they think of heart scans. 3D TTE is one of the most recent techniques for heart imaging, and its modernity definitely shows- it's easier to get an idea of what things are with 3D TTEs, as their colors do a great job of giving depth to the animations.

Here's a gif of 3D TTE in action:

https://media.giphy.com/media/EpMr2qzXxrJny/giphy.gif

I'll post some more stuff regarding The Heartwell Project as soon as I get an update from our animator.

Today, as I suspected, Dr. Nguyen did not have any cases. Despite this, it was still a great morning; after getting coffee and a banana, I met with Dr. Nguyen at valve conference in the HVI. It has been at least three weeks since I have attended a conference, and today's visit represented a healthy return to the lively, doctor-filled room. I got there early enough to get an agenda hand-out from one of the doctors mediating the conference, which covered the patient names and the doctors responsible for their cases. It became way easier to soak up and understand what they were referencing in conversation, as the patients' conditions were on the pages. After finishing patient rounds, Dr. Nguyen, his assistant Loren and I went down to imaging to see one of his patient's 3D TTEs (3D transthoracic echocardiographs). These are very different from echocardiograms, which are what most people imagine when they think of heart scans. 3D TTE is one of the most recent techniques for heart imaging, and its modernity definitely shows- it's easier to get an idea of what things are with 3D TTEs, as their colors do a great job of giving depth to the animations.

Here's a gif of 3D TTE in action:

https://media.giphy.com/media/EpMr2qzXxrJny/giphy.gif

I'll post some more stuff regarding The Heartwell Project as soon as I get an update from our animator.

Sunday, May 1, 2016

Update 5/1/16: "Dr. Heartwell" Animation Preview and Short Hiatus

"Two weeks without a blog post? Is he slacking off?"

It's been a bit over two weeks since I've posted anything, so I thought I'd address that (first). Since I only attend my internship once a week- on Fridays- these posts are totally contingent on me being able to go on that specific day, from 6:50 am to around 11:00 am. So, for the past two Fridays, scheduling conflicts have come up that have prevented me from going. Dr. Nguyen has his occasional business trips, and I have school. I'll almost definitely have a post for this upcoming Friday, but it's too early to tell what I'll be doing if I go; I'm hoping for a case, but Dr. Nguyen could very well have valve conference that morning. There's one surgery that I'm just dying to see, which is a VSARR (Valve-Sparing Aortic Root Replacement)- I talked about it a while ago in a detailed post, but I missed the last one that Dr. Nguyen performed (at least to my knowledge). I won't explain it here, as that would be...long, but what's being done in that surgery is nothing short of incredible. Not to mention the cool name. I'm definitely going to try to see one.

On to more important things, the gang and I have been patiently awaiting updates from our animator about progress on the Dr. Heartwell project. I've had a look at what's been created, and I'm really impressed with how far our basic ideas have come. We started this a few months ago with some simple goals- all we had to show for it was a few pages of rough pencil storyboard sketches and some Microsoft Word documents full of notes. It is quickly starting to unfold as something tangible, something ready to be shown to others with satisfaction; that's why I'd like to give a quick sample of the animation on this blog post. Its creation process has been a really unique experience for me, and it isn't comparable to any sort of work I've done in the past. It's grounded in the real world, but goes far past volunteer service, as I'm working with professionals from various fields to get it done. It'll definitely stand as the best group project of my high school career- too bad I'm not getting graded on it.

P.S., please tell me if the video isn't working.

It's been a bit over two weeks since I've posted anything, so I thought I'd address that (first). Since I only attend my internship once a week- on Fridays- these posts are totally contingent on me being able to go on that specific day, from 6:50 am to around 11:00 am. So, for the past two Fridays, scheduling conflicts have come up that have prevented me from going. Dr. Nguyen has his occasional business trips, and I have school. I'll almost definitely have a post for this upcoming Friday, but it's too early to tell what I'll be doing if I go; I'm hoping for a case, but Dr. Nguyen could very well have valve conference that morning. There's one surgery that I'm just dying to see, which is a VSARR (Valve-Sparing Aortic Root Replacement)- I talked about it a while ago in a detailed post, but I missed the last one that Dr. Nguyen performed (at least to my knowledge). I won't explain it here, as that would be...long, but what's being done in that surgery is nothing short of incredible. Not to mention the cool name. I'm definitely going to try to see one.

On to more important things, the gang and I have been patiently awaiting updates from our animator about progress on the Dr. Heartwell project. I've had a look at what's been created, and I'm really impressed with how far our basic ideas have come. We started this a few months ago with some simple goals- all we had to show for it was a few pages of rough pencil storyboard sketches and some Microsoft Word documents full of notes. It is quickly starting to unfold as something tangible, something ready to be shown to others with satisfaction; that's why I'd like to give a quick sample of the animation on this blog post. Its creation process has been a really unique experience for me, and it isn't comparable to any sort of work I've done in the past. It's grounded in the real world, but goes far past volunteer service, as I'm working with professionals from various fields to get it done. It'll definitely stand as the best group project of my high school career- too bad I'm not getting graded on it.

P.S., please tell me if the video isn't working.

Sunday, April 17, 2016

4/15/16

Today, I went to a case w/ Dr. Nguyen. Valve clinic wasn't a lot of fun to blog about, so I wanted to spice things up for a while with a new procedure in each post. Lectures- like the one I covered a few months ago about vena cava filters- are great, but don't crop up often enough for me to consistently post about them. Feedback on what I'm covering is totally welcome, and I could probably even take requests about certain topics.

The case this morning was a sternotomy-CABG, which is a procedure that I've been looking forward to seeing for a while- the mini-repairs and replacements I've talked about in the past few weeks offer much less visibility, and aren't as interesting to watch. CABG is an acronym for coronary artery bypass graft. In this procedure, the doctors remove a faulty segment of a coronary artery in the myocardium (walls) of the heart, and replace it by grafting on an artery from elsewhere. The graft usually comes from the right or left interior mammary arteries, which run under the breast. This operation is performed if there's a blockage in the coronary arteries that can't be solved by PCI/stenting; the heart needs adequate amounts of blood to pump, so if one of its arteries is blocked by plaque (atherosclerosis), that needs to be taken care of. A lack of blood to the heart's muscles can lead to myocardial infarction, better known as a heart attack. Although I've seen this surgery before, I was really looking forward to seeing it in its entirety today. Complications getting the left mammary artery for the graft led to it taking longer than expected, but there was one good thing: the anesthesiologists let me hang out in their corner of the room. They sit adjacent to the patient, amongst a labyrinth of tubes, wires and equipment. They have a direct view into the chest cavity- and it's the best view in the house. It's an entirely different experience to see the patient's chest, spread open with a still-beating heart inside, and be able to look down to see his head. You realize that it's a person who's being operated on. I've had the same view before, but now that I have more experience and actually know what the doctors are doing, I guess it just gave me new perspective. I made it up to bypass before I had to head out, which is a bummer, but the new outlook I gained made it better than all of the past cases I've seen.

Also, we've decided to call the project The Educated Patient Series. We also picked a name for the doctor/mascot who will be walking viewers through all of the animations: Dr. Heartwell (clever, right?). We're still working with the animator to make revisions and fine-tune the video, but all of the right things are there. More to come about both my neat OR visits and The Educated Patient Series over the next few weeks.

The case this morning was a sternotomy-CABG, which is a procedure that I've been looking forward to seeing for a while- the mini-repairs and replacements I've talked about in the past few weeks offer much less visibility, and aren't as interesting to watch. CABG is an acronym for coronary artery bypass graft. In this procedure, the doctors remove a faulty segment of a coronary artery in the myocardium (walls) of the heart, and replace it by grafting on an artery from elsewhere. The graft usually comes from the right or left interior mammary arteries, which run under the breast. This operation is performed if there's a blockage in the coronary arteries that can't be solved by PCI/stenting; the heart needs adequate amounts of blood to pump, so if one of its arteries is blocked by plaque (atherosclerosis), that needs to be taken care of. A lack of blood to the heart's muscles can lead to myocardial infarction, better known as a heart attack. Although I've seen this surgery before, I was really looking forward to seeing it in its entirety today. Complications getting the left mammary artery for the graft led to it taking longer than expected, but there was one good thing: the anesthesiologists let me hang out in their corner of the room. They sit adjacent to the patient, amongst a labyrinth of tubes, wires and equipment. They have a direct view into the chest cavity- and it's the best view in the house. It's an entirely different experience to see the patient's chest, spread open with a still-beating heart inside, and be able to look down to see his head. You realize that it's a person who's being operated on. I've had the same view before, but now that I have more experience and actually know what the doctors are doing, I guess it just gave me new perspective. I made it up to bypass before I had to head out, which is a bummer, but the new outlook I gained made it better than all of the past cases I've seen.

Also, we've decided to call the project The Educated Patient Series. We also picked a name for the doctor/mascot who will be walking viewers through all of the animations: Dr. Heartwell (clever, right?). We're still working with the animator to make revisions and fine-tune the video, but all of the right things are there. More to come about both my neat OR visits and The Educated Patient Series over the next few weeks.

Friday, April 8, 2016

4/8/16

Here's that animation update I talked about last week.

I made some strides towards completing the Kickstarter, and got some feedback from the rest of the group on how it was progressing along. One of the main hurdles I was concerned about was the reward for donors. If you're not familiar with Kickstarter's system, they require the project owners to compensate its contributors (which is often based on how much they give) if the project meets its funding goal. For donors who give $10-$20, mailing stickers or naming them at the end of our videos would be enough- but problems arise when it comes to dealing with $50-$100 donations. Some ideas we thought of were t-shirts, coffee mugs, and even handwritten thank-you notes. I've noticed that plush hearts are given to recovering patients in the HVI ICU- maybe we could brand them with our project's name, or some design, and give those out. What we're doing is not like a lot of the other Kickstarter projects out there; it's really just a (great) community service, not a product. This makes it hard to deal with large donations. Dr. Nguyen recently reached out to Memorial Hermann's PR and marketing department, who loved the idea that we're proposing. They'll probably want to see what it looks like when we've completely finished the first animation, and if they are interested or impressed, we might not even need the Kickstarter. But hey, it never hurts to prepare.

I made some strides towards completing the Kickstarter, and got some feedback from the rest of the group on how it was progressing along. One of the main hurdles I was concerned about was the reward for donors. If you're not familiar with Kickstarter's system, they require the project owners to compensate its contributors (which is often based on how much they give) if the project meets its funding goal. For donors who give $10-$20, mailing stickers or naming them at the end of our videos would be enough- but problems arise when it comes to dealing with $50-$100 donations. Some ideas we thought of were t-shirts, coffee mugs, and even handwritten thank-you notes. I've noticed that plush hearts are given to recovering patients in the HVI ICU- maybe we could brand them with our project's name, or some design, and give those out. What we're doing is not like a lot of the other Kickstarter projects out there; it's really just a (great) community service, not a product. This makes it hard to deal with large donations. Dr. Nguyen recently reached out to Memorial Hermann's PR and marketing department, who loved the idea that we're proposing. They'll probably want to see what it looks like when we've completely finished the first animation, and if they are interested or impressed, we might not even need the Kickstarter. But hey, it never hurts to prepare.

Sunday, April 3, 2016

3/31/16

I don't usually go on Thursdays, which made today's schedule especially weird. I went with Dr. Nguyen to post-op patient checkups, which consisted of mostly severe-condition patients; it's always good to see the patients' families responding well to the recovery process, even if the news they're getting isn't ideal. A lot of the early recovery process involves the management of fluids secreted into the areas around the heart- a chest tube is attached through a chest incision to deal with drainage of blood, pus, and other nasty stuff. It uses suction to evacuate the heart's surrounding tissues of threatening fluid accumulations (called pericardial effusion), and is removed once the leakage stops. Multiple tubes can be installed, and can be removed based on which areas need tending to. Neat, right?

For the case this morning, I arrived with Dr. Nguyen. I got to see the entire pre-surgery process: antibacterial prep, moving bypass equipment into place, etc. The case was a mini-mitral valve repair, which isn't the most fun surgery to watch (mostly due to lack of visibility), but it's complicated and I definitely appreciate the amount of skill involved. I've talked about mini procedure in earlier blog posts- it's basically like digging a tunnel to the heart, starting near the ribs, on the right side of the upper chest. The left femoral artery and vein are cannulated and connected to a bypass machine, allowing the heart to be operated on. The mitral valve is so far back in this cavity that the doctors have to use special elongated tools to reach it, and are forced to jump through all sorts of hoops. It's safer than open-heart surgery and has a much lower recovery time, but is more difficult. From what I can tell, it's hard mode for heart surgery. Back to our specific case, the patient's mitral valve was prolapsed, which is something I haven't heard of before. The mitral valve has two leaflets-posterior and anterior- flaps that open and close when blood is pumped. These leaflets are attached to pieces of tissue called chordae tendinae. In prolapse, a tendon becomes loose, which causes the leaflet it is attached to to not pull shut. The prolapsed leaflet will begin to "climb" over the other one, causing mitral regurgitation, as the blood drips back into the left atrium after being pumped. To solve this problem, a ring has to be sized to fit the mitral annulus, and sutured in to keep the valve from leaking. In addition, a piece of tissue from the prolapsed valve is cut out to prevent overlap. I was familiar with mitral regurgitation/insufficiency before going into this surgery, along with mini procedures, but just about everything else was new. Every time I think I'm getting a handle on basic heart knowledge, something just has to take me down a rung...

Pictures of mitral prolapse and repair are below (non-graphic).

I intended to post a bit more this week, but I was waiting on some new info to roll in about the animation. Now that I've got a sizable amount of info (aka blog-worthy, because I love making long posts), I'll probably have something next week about that. Thanks for reading!

Normal v. Prolapsed, with a cutaway view of the left atrium and ventricle.

Repaired mitral valve, with annulus ring and fixed posterior leaflet overlap.

For the case this morning, I arrived with Dr. Nguyen. I got to see the entire pre-surgery process: antibacterial prep, moving bypass equipment into place, etc. The case was a mini-mitral valve repair, which isn't the most fun surgery to watch (mostly due to lack of visibility), but it's complicated and I definitely appreciate the amount of skill involved. I've talked about mini procedure in earlier blog posts- it's basically like digging a tunnel to the heart, starting near the ribs, on the right side of the upper chest. The left femoral artery and vein are cannulated and connected to a bypass machine, allowing the heart to be operated on. The mitral valve is so far back in this cavity that the doctors have to use special elongated tools to reach it, and are forced to jump through all sorts of hoops. It's safer than open-heart surgery and has a much lower recovery time, but is more difficult. From what I can tell, it's hard mode for heart surgery. Back to our specific case, the patient's mitral valve was prolapsed, which is something I haven't heard of before. The mitral valve has two leaflets-posterior and anterior- flaps that open and close when blood is pumped. These leaflets are attached to pieces of tissue called chordae tendinae. In prolapse, a tendon becomes loose, which causes the leaflet it is attached to to not pull shut. The prolapsed leaflet will begin to "climb" over the other one, causing mitral regurgitation, as the blood drips back into the left atrium after being pumped. To solve this problem, a ring has to be sized to fit the mitral annulus, and sutured in to keep the valve from leaking. In addition, a piece of tissue from the prolapsed valve is cut out to prevent overlap. I was familiar with mitral regurgitation/insufficiency before going into this surgery, along with mini procedures, but just about everything else was new. Every time I think I'm getting a handle on basic heart knowledge, something just has to take me down a rung...

Pictures of mitral prolapse and repair are below (non-graphic).

I intended to post a bit more this week, but I was waiting on some new info to roll in about the animation. Now that I've got a sizable amount of info (aka blog-worthy, because I love making long posts), I'll probably have something next week about that. Thanks for reading!

Normal v. Prolapsed, with a cutaway view of the left atrium and ventricle.

Repaired mitral valve, with annulus ring and fixed posterior leaflet overlap.

Friday, March 25, 2016

3/25/16

A lot has changed, and for the better- I almost feel like bullet-pointing this post. Deadlines have been re-adjusted; the potential TV spot has been moved from mid-April to around June. We've gone from having to rush out a finished product to having the time to really make sure it's what we want. We are in talks with an animation studio that has developed a rough cut of what the animation could look like, moving us past our storyboard/script phase. It looks good, and further discussions will take place over the long weekend to see what changes need to be made; maybe more of a story focus, rather than just an info drop. It's meant to be rather short, at two to three minutes, so I'm not sure how much we need to pack into that time. What I'm also working around right now is the endgame for the project. I'm basically answering the question: If it's successful and the TV spot lets thousands of Houstonians know about it,where do we go from there? Would we pitch the idea to Memorial Hermann, with the prospect of them providing money for our future efforts? Or, would we use the support garnered from the TV spot to form our own business (likely through crowdfunding sites like Kickstarter, GoFundMe, etc)? I'm still deciding. And I'll be asking the other members of the team for their opinions on it, as well. It's great to get caught up in the moment with this project, but seeing the (possible) big picture isn't always a bad thing.

Monday, March 21, 2016

Schedule Update and 3/18/16

Schedule Update

And just like that, spring break is over. Going forward, the next two weeks will represent an interesting shift in the frequency of my blog posts; I have the promising opportunity to work on the project animation for 14 days, uninterrupted. That sounds like I'm skipping class, but it couldn't be further from the truth- it is my class. My school hosts a series of two-week classes at the end of March leading into April, which is known as A-term. I decided to do my own, as the opportunity here is too great to miss out on. As the project is already underway, getting it off the ground and forming a concrete base of work is already done with. The storyboard has almost been completed, and we're moving into the contact phase. I'll be reaching out to animation studios for quotes/estimates based on what we want out of the project, mostly playing it by ear- Dr. Nguyen might want certain things out of this development stage, and some new ideas might be brought into the fray. I'll be giving out updates and pieces of information pertaining to the project over the next two weeks. Stay tuned.

3/18/16

Because of the importance of the project, most of my internship visits as of late have been rather short, and today was no exception. I shadowed Dr. Nguyen's post-op patient visits in the ICU, which I haven't really talked about yet- I think I've mentioned them in passing, but I've never really detailed what goes on there. It's not really comparable to any other part of my time at the hospital, as seeing post-op patients is definitely more emotional than watching a surgery or discussing their heart conditions in valve conference. Sometimes the patient is close to death, and I see a snapshot of that when I walk into the room. Other times they're doing very well, surrounded by family members who love them and can't wait until they fully recover. The latter example is (thankfully) the much more common one, but I think there's something to be learned from both.

Sunday, March 6, 2016

3/4/16

Today I met with Dr. Nguyen around 1:00 pm, with no idea what we'd be doing- but, he told me to wear my scrubs. I didn't end up using them to enter the OR or anything, which is good because I wanted to dedicate this blog post to our project. Things worked out! After luckily running into Dr. Nguyen in the hallways of the cardiovascular ICU on the 8th floor, I went with him to go deal with a patient's incision drainage- not the best thing to see after lunch. A few sutures later, we were on our way to his office for a short meeting about the project. I went over what "the project" is in my Feb. 12th blog post, but I'll review it again here: it's the seed for a greater effort to introduce layman audiences to complicated heart diseases, and uses simple animation as a means of conveying information. I've been thinking of naming it "(insert heart condition):What's Going On?," but that's tentative. We've crafted a story around it, and will be using that story to bring in viewership and ensure a degree of entertainment. Length-wise, it's aimed at around five minutes; keeping it short is part of the accessibility. People are busy, and if they have a loved one dealing with a heart condition, they won't want to sit down for a thirty-minute lecture on the intricacies of that condition. They need the basics, and that's exactly what we hope to deliver.

The first animation we're working on is about aortic stenosis, the tightening of the aortic valve. The animation has been through a full storyboard draft, and the topic of discussion today was how we'd be moving forward with it. We both decided that pushing it through another draft would be necessary, as refined work is what we both want to see- from the visuals to the dialogue. Dr. Nguyen revealed a potential TV opportunity for it in the near future, which, if used, could really get the entire project on its feet. I'm hopeful that connections can be made through that opportunity, but first we've got to create something that's polished and worth people's time. Saying this makes me sound like a stereotypical teenager, but there are some holes to be filled in Memorial Hermann's social media presence. Their Youtube channel is full of anecdotal cases and recovery stories, which- while impactful- don't deliver overarching information. Every case is different, and although they might give prospective patients something to identify with, it's not contributing to their education about diseases. I definitely appreciate Memorial Hermann's efforts there, but it's just a source of encouraging entertainment. Pulling through with a decent idea about heart disease education is a service not just to future patients, but to the hospital's standing in the tech-savvy world we live in. People want to learn, and with the internet making it easier than ever, What's Going On? has incredible potential.

The first animation we're working on is about aortic stenosis, the tightening of the aortic valve. The animation has been through a full storyboard draft, and the topic of discussion today was how we'd be moving forward with it. We both decided that pushing it through another draft would be necessary, as refined work is what we both want to see- from the visuals to the dialogue. Dr. Nguyen revealed a potential TV opportunity for it in the near future, which, if used, could really get the entire project on its feet. I'm hopeful that connections can be made through that opportunity, but first we've got to create something that's polished and worth people's time. Saying this makes me sound like a stereotypical teenager, but there are some holes to be filled in Memorial Hermann's social media presence. Their Youtube channel is full of anecdotal cases and recovery stories, which- while impactful- don't deliver overarching information. Every case is different, and although they might give prospective patients something to identify with, it's not contributing to their education about diseases. I definitely appreciate Memorial Hermann's efforts there, but it's just a source of encouraging entertainment. Pulling through with a decent idea about heart disease education is a service not just to future patients, but to the hospital's standing in the tech-savvy world we live in. People want to learn, and with the internet making it easier than ever, What's Going On? has incredible potential.

Sunday, February 28, 2016

2/26/16

Today was a good day to be at Memorial Hermann, and I couldn't have had a better return to my normal internship schedule. At 7:00, I attended a lecture with Dr. Nguyen on the pathogenesis of heart failure, given by Dr. Maximilian Buja. He presented a wealth of information about the complexities of heart disease, and much of it was completely new to me. Cardiomyocytes, the muscle cells that make up the heart, were front-and-center in his presentation; these cells are extremely powerful, and them functioning correctly is critical to the heart as a whole being able to perform. They produce ATP (basically the body's "energy currency") at an extremely quick rate, making them great at working constantly. Dr. Buja discussed the cardiomyocytes in relation to heart conditions and different diseases therein, with ischemic cardiomyopathy (ischemic CM) as one of the highlights. In ischemic CM, the heart's left ventricle is weak and can't pump blood out to the body efficiently- this is usually a result of inadequate blood supply to the heart's coronary arteries (that causes heart attacks). So, the heart tissues aren't getting enough blood/energy, which makes them unable to pump the other collections of blood through the heart's systolic chambers. One problem with the cardiomyocytes not getting enough energy is that they don't just replace themselves, and permanent damage can be done. Once the cells die, patches of necrotic tissue begin to form on the heart, and will stay until surrounding blood flow leads to the necrotic area scarring and being partially repaired. Since Dr. Buja was presenting to a room full of doctors, a lot of the above info was skipped over, so his primary focus was on the options for supporting the heart throughout ischemic CM: defibrillators, ventricle assist devices, balloon pumps, the works. There was a lot more about transplant rejection and antibody responses, but that'll take a bit to explain in detail...plus, I'm still processing that myself. Isn't learning stuff great?

Valve conference was a fairly normal length today, with a handful of cases. For those who aren't familiar with what it is, I get to watch a group of cardiologists and cardiothoracic surgeons discuss what should be done with pre-op heart patients. Powerpoints are shown, opinions differ, and occasionally, jokes are thrown around- it's generally a good time. A couple of patients had aortic stenosis (tightening of the aortic valve), a few others had coronary issues, but there was only one case that really caught my eye. There's usually one of them in every conference, a case that the doctors argue over because of its complexity or because of their individual experiences with cases like it. This one involved a 70 year old woman with symptoms of aortic stenosis, moderate mitral stenosis, and lung damage. The choice to proceed hinged on what they needed to do first, and how effective that first surgery would be in remedying the other issues. It was a quiet, well-mannered battle of aortic vs. mitral repair. One doctor chimed in to say that non-surgical procedures are what they really need to think about, because the risk is just too high to immediately consider surgery. After a lengthy discussion, I recall that they decided it was an inoperable situation; they would do the best to make the woman comfortable, but going through surgery would just be a waste of her remaining time. Being realistic is a key part of making these calls, but listening to these conversations is sobering in a world of advanced medicine. Not everyone can be saved, and the outcome won't always be great or optimal, but that's life.

That's about all I have for this week. The storyboard for the aortic stenosis project is in its second draft, and since this post is so long, I'll shorten details for the coming Friday's post and put some info/photos of it there. Whether you made it all the way through or not, thanks for reading!

Valve conference was a fairly normal length today, with a handful of cases. For those who aren't familiar with what it is, I get to watch a group of cardiologists and cardiothoracic surgeons discuss what should be done with pre-op heart patients. Powerpoints are shown, opinions differ, and occasionally, jokes are thrown around- it's generally a good time. A couple of patients had aortic stenosis (tightening of the aortic valve), a few others had coronary issues, but there was only one case that really caught my eye. There's usually one of them in every conference, a case that the doctors argue over because of its complexity or because of their individual experiences with cases like it. This one involved a 70 year old woman with symptoms of aortic stenosis, moderate mitral stenosis, and lung damage. The choice to proceed hinged on what they needed to do first, and how effective that first surgery would be in remedying the other issues. It was a quiet, well-mannered battle of aortic vs. mitral repair. One doctor chimed in to say that non-surgical procedures are what they really need to think about, because the risk is just too high to immediately consider surgery. After a lengthy discussion, I recall that they decided it was an inoperable situation; they would do the best to make the woman comfortable, but going through surgery would just be a waste of her remaining time. Being realistic is a key part of making these calls, but listening to these conversations is sobering in a world of advanced medicine. Not everyone can be saved, and the outcome won't always be great or optimal, but that's life.

That's about all I have for this week. The storyboard for the aortic stenosis project is in its second draft, and since this post is so long, I'll shorten details for the coming Friday's post and put some info/photos of it there. Whether you made it all the way through or not, thanks for reading!

Thursday, February 25, 2016

2/24/16

Today I decided to come in to watch one of Dr. Nguyen's cases, a mini-mitral valve replacement. I didn't have any background knowledge about the patient, but being there was interesting enough; this was the first mini I've seen, and also the first operation I had seen performed on the mitral valve. The mitral valve is the first valve to be reached by oxygenated blood coming from the lungs, and is located between the left atrium and the left ventricle. A mini is a minimally-invasive surgery, which relies on 1-4 incisions around the thorax to perform the operation, as opposed to a sternotomy that splits the chest open entirely. Although there are many factors to consider, some people just don't like the recovery time involved with a sternotomy, and might pick a mini operation over it if given the choice.