The surgery starts with an incision in the lower left of the chest, near the groin; this leads directly into the femoral vein. A cannula (fancy word for tube) is inserted into the vein, and is connected to a heart-lung machine. Another cannula is drawn from the heart-lung machine to the femoral artery, creating a system that draws out blood, reoxygenates it outside of the patient, and feeds it back into the lower body. Another incision is made on the right side of the chest, just under the breast, and the hole is widened with rib spreaders. With his incision opens up a view of the pericardium, the area surrounding and holding the heart, from the ascending aorta to the diaphragm in length. The pericardium is then cut open, and sutured in place to reveal the aorta. Cardioplegia is administered- which slows and eventually stops the heart- so that the journey to the mitral valve can begin. This process is quite extensive( and definitely looks the part), as the doctor has to get all the way to the mitral valve from a hole in the pericardium. It really ends up looking like a tunnel, and gets even more confusing once the sutures and ties holding tissue in place are set. The sutures divide the tissue layers, allowing a small hole of viewing space into the mitral valve. Because of how tightly-packed the area was with sutures, clamps and cannulas, it was satisfying to be able to identify the chordae tendonae peeking out from behind the relaxed mitral valve. It was sort of like a medical version of "Where's Waldo."It was around this point that I realized that Dr. Nguyen was doing a full valve replacement. He started clipping away at the mitral valve's leaflets, and removed the valve surprisingly quickly. The replacement valve was to be mechanical, so he began attaching the sutures to the lip lining the mechanical valve, a part of one of the most complicated processes I've seen in the OR- I'm talking about the scaffolding/lowering-of-the-replacement-valve process, which secures the new valve in place. The ends of those sutures attached I wasn't able to stay to see the heart tissues sutured back together, which is a bummer, but I'm glad that I got to see most of the installation process. Because the patient received a mechanical valve, they will have to take Coumadin or Warfarin (blood thinners) daily for the rest of their lives; the structure of the mechanical valve allows blood clots to develop more easily, so this is a safety precaution.

Having seen both kinds of surgery, sternotomies and minis, sternotomies are much more appealing from the viewer's perspective. One would assume that it's easier on the doctors, too- the chest is split, and there's plenty of viewing room. It's a direct look at the heart, and all of the doctors surrounding the patient can see what is going on. Minis, on the other hand, are performed through the right of the chest, and docs assisting with the surgery have to rely on the performing doctor's live headcam footage to get a peek. I would've had no idea what was going on without Dr. Nguyen's headcam footage being projected on the nearby flatscreen TV. Even the surgical instruments involved in it are long, complicated and awkward; the highly trained professionals involved with this surgery struggled, at times, to position cannulas and other materials around the chest incision.

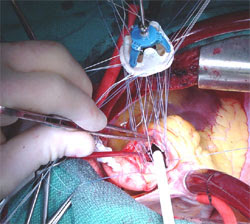

Above is a clean picture of the surgery, with clamps, cannulas, sutures and the rib spreader in place. This is still pre-valve installation

Above is a real picture (not mine) of the suture scaffolding, lowering the replacement valve in.

I thought that this deserved a long blog post, because seeing actual surgery is one of the most interesting things about this internship. The human body is incredible, and what we're able to do with it in regards to medical care is even more astonishing. Hopefully I'll be able to spectate one surgery every month or so, but because they're so long and right in the middle of the day, planning gets a bit tricky.. I'll have another post about this Friday's events (as promised) up by the end of the weekend.

Your attention to detail as you observe these surgeries is obvious. Thank you for writing in such a way that the reader feels as though they are there.

ReplyDeleteI really enjoyed reading about the inside of the heart and possibly what to expect when D has his surgery. Your a great writer Brayden and very knowledgable with the human body. Keep it up.

ReplyDeleteI learned a lot reading your post - great explanation.

ReplyDeleteSo cool that you are already interning and gaining experience.