A lot has changed, and for the better- I almost feel like bullet-pointing this post. Deadlines have been re-adjusted; the potential TV spot has been moved from mid-April to around June. We've gone from having to rush out a finished product to having the time to really make sure it's what we want. We are in talks with an animation studio that has developed a rough cut of what the animation could look like, moving us past our storyboard/script phase. It looks good, and further discussions will take place over the long weekend to see what changes need to be made; maybe more of a story focus, rather than just an info drop. It's meant to be rather short, at two to three minutes, so I'm not sure how much we need to pack into that time. What I'm also working around right now is the endgame for the project. I'm basically answering the question: If it's successful and the TV spot lets thousands of Houstonians know about it,where do we go from there? Would we pitch the idea to Memorial Hermann, with the prospect of them providing money for our future efforts? Or, would we use the support garnered from the TV spot to form our own business (likely through crowdfunding sites like Kickstarter, GoFundMe, etc)? I'm still deciding. And I'll be asking the other members of the team for their opinions on it, as well. It's great to get caught up in the moment with this project, but seeing the (possible) big picture isn't always a bad thing.

Friday, March 25, 2016

Monday, March 21, 2016

Schedule Update and 3/18/16

Schedule Update

And just like that, spring break is over. Going forward, the next two weeks will represent an interesting shift in the frequency of my blog posts; I have the promising opportunity to work on the project animation for 14 days, uninterrupted. That sounds like I'm skipping class, but it couldn't be further from the truth- it is my class. My school hosts a series of two-week classes at the end of March leading into April, which is known as A-term. I decided to do my own, as the opportunity here is too great to miss out on. As the project is already underway, getting it off the ground and forming a concrete base of work is already done with. The storyboard has almost been completed, and we're moving into the contact phase. I'll be reaching out to animation studios for quotes/estimates based on what we want out of the project, mostly playing it by ear- Dr. Nguyen might want certain things out of this development stage, and some new ideas might be brought into the fray. I'll be giving out updates and pieces of information pertaining to the project over the next two weeks. Stay tuned.

3/18/16

Because of the importance of the project, most of my internship visits as of late have been rather short, and today was no exception. I shadowed Dr. Nguyen's post-op patient visits in the ICU, which I haven't really talked about yet- I think I've mentioned them in passing, but I've never really detailed what goes on there. It's not really comparable to any other part of my time at the hospital, as seeing post-op patients is definitely more emotional than watching a surgery or discussing their heart conditions in valve conference. Sometimes the patient is close to death, and I see a snapshot of that when I walk into the room. Other times they're doing very well, surrounded by family members who love them and can't wait until they fully recover. The latter example is (thankfully) the much more common one, but I think there's something to be learned from both.

Sunday, March 6, 2016

3/4/16

Today I met with Dr. Nguyen around 1:00 pm, with no idea what we'd be doing- but, he told me to wear my scrubs. I didn't end up using them to enter the OR or anything, which is good because I wanted to dedicate this blog post to our project. Things worked out! After luckily running into Dr. Nguyen in the hallways of the cardiovascular ICU on the 8th floor, I went with him to go deal with a patient's incision drainage- not the best thing to see after lunch. A few sutures later, we were on our way to his office for a short meeting about the project. I went over what "the project" is in my Feb. 12th blog post, but I'll review it again here: it's the seed for a greater effort to introduce layman audiences to complicated heart diseases, and uses simple animation as a means of conveying information. I've been thinking of naming it "(insert heart condition):What's Going On?," but that's tentative. We've crafted a story around it, and will be using that story to bring in viewership and ensure a degree of entertainment. Length-wise, it's aimed at around five minutes; keeping it short is part of the accessibility. People are busy, and if they have a loved one dealing with a heart condition, they won't want to sit down for a thirty-minute lecture on the intricacies of that condition. They need the basics, and that's exactly what we hope to deliver.

The first animation we're working on is about aortic stenosis, the tightening of the aortic valve. The animation has been through a full storyboard draft, and the topic of discussion today was how we'd be moving forward with it. We both decided that pushing it through another draft would be necessary, as refined work is what we both want to see- from the visuals to the dialogue. Dr. Nguyen revealed a potential TV opportunity for it in the near future, which, if used, could really get the entire project on its feet. I'm hopeful that connections can be made through that opportunity, but first we've got to create something that's polished and worth people's time. Saying this makes me sound like a stereotypical teenager, but there are some holes to be filled in Memorial Hermann's social media presence. Their Youtube channel is full of anecdotal cases and recovery stories, which- while impactful- don't deliver overarching information. Every case is different, and although they might give prospective patients something to identify with, it's not contributing to their education about diseases. I definitely appreciate Memorial Hermann's efforts there, but it's just a source of encouraging entertainment. Pulling through with a decent idea about heart disease education is a service not just to future patients, but to the hospital's standing in the tech-savvy world we live in. People want to learn, and with the internet making it easier than ever, What's Going On? has incredible potential.

The first animation we're working on is about aortic stenosis, the tightening of the aortic valve. The animation has been through a full storyboard draft, and the topic of discussion today was how we'd be moving forward with it. We both decided that pushing it through another draft would be necessary, as refined work is what we both want to see- from the visuals to the dialogue. Dr. Nguyen revealed a potential TV opportunity for it in the near future, which, if used, could really get the entire project on its feet. I'm hopeful that connections can be made through that opportunity, but first we've got to create something that's polished and worth people's time. Saying this makes me sound like a stereotypical teenager, but there are some holes to be filled in Memorial Hermann's social media presence. Their Youtube channel is full of anecdotal cases and recovery stories, which- while impactful- don't deliver overarching information. Every case is different, and although they might give prospective patients something to identify with, it's not contributing to their education about diseases. I definitely appreciate Memorial Hermann's efforts there, but it's just a source of encouraging entertainment. Pulling through with a decent idea about heart disease education is a service not just to future patients, but to the hospital's standing in the tech-savvy world we live in. People want to learn, and with the internet making it easier than ever, What's Going On? has incredible potential.

Sunday, February 28, 2016

2/26/16

Today was a good day to be at Memorial Hermann, and I couldn't have had a better return to my normal internship schedule. At 7:00, I attended a lecture with Dr. Nguyen on the pathogenesis of heart failure, given by Dr. Maximilian Buja. He presented a wealth of information about the complexities of heart disease, and much of it was completely new to me. Cardiomyocytes, the muscle cells that make up the heart, were front-and-center in his presentation; these cells are extremely powerful, and them functioning correctly is critical to the heart as a whole being able to perform. They produce ATP (basically the body's "energy currency") at an extremely quick rate, making them great at working constantly. Dr. Buja discussed the cardiomyocytes in relation to heart conditions and different diseases therein, with ischemic cardiomyopathy (ischemic CM) as one of the highlights. In ischemic CM, the heart's left ventricle is weak and can't pump blood out to the body efficiently- this is usually a result of inadequate blood supply to the heart's coronary arteries (that causes heart attacks). So, the heart tissues aren't getting enough blood/energy, which makes them unable to pump the other collections of blood through the heart's systolic chambers. One problem with the cardiomyocytes not getting enough energy is that they don't just replace themselves, and permanent damage can be done. Once the cells die, patches of necrotic tissue begin to form on the heart, and will stay until surrounding blood flow leads to the necrotic area scarring and being partially repaired. Since Dr. Buja was presenting to a room full of doctors, a lot of the above info was skipped over, so his primary focus was on the options for supporting the heart throughout ischemic CM: defibrillators, ventricle assist devices, balloon pumps, the works. There was a lot more about transplant rejection and antibody responses, but that'll take a bit to explain in detail...plus, I'm still processing that myself. Isn't learning stuff great?

Valve conference was a fairly normal length today, with a handful of cases. For those who aren't familiar with what it is, I get to watch a group of cardiologists and cardiothoracic surgeons discuss what should be done with pre-op heart patients. Powerpoints are shown, opinions differ, and occasionally, jokes are thrown around- it's generally a good time. A couple of patients had aortic stenosis (tightening of the aortic valve), a few others had coronary issues, but there was only one case that really caught my eye. There's usually one of them in every conference, a case that the doctors argue over because of its complexity or because of their individual experiences with cases like it. This one involved a 70 year old woman with symptoms of aortic stenosis, moderate mitral stenosis, and lung damage. The choice to proceed hinged on what they needed to do first, and how effective that first surgery would be in remedying the other issues. It was a quiet, well-mannered battle of aortic vs. mitral repair. One doctor chimed in to say that non-surgical procedures are what they really need to think about, because the risk is just too high to immediately consider surgery. After a lengthy discussion, I recall that they decided it was an inoperable situation; they would do the best to make the woman comfortable, but going through surgery would just be a waste of her remaining time. Being realistic is a key part of making these calls, but listening to these conversations is sobering in a world of advanced medicine. Not everyone can be saved, and the outcome won't always be great or optimal, but that's life.

That's about all I have for this week. The storyboard for the aortic stenosis project is in its second draft, and since this post is so long, I'll shorten details for the coming Friday's post and put some info/photos of it there. Whether you made it all the way through or not, thanks for reading!

Valve conference was a fairly normal length today, with a handful of cases. For those who aren't familiar with what it is, I get to watch a group of cardiologists and cardiothoracic surgeons discuss what should be done with pre-op heart patients. Powerpoints are shown, opinions differ, and occasionally, jokes are thrown around- it's generally a good time. A couple of patients had aortic stenosis (tightening of the aortic valve), a few others had coronary issues, but there was only one case that really caught my eye. There's usually one of them in every conference, a case that the doctors argue over because of its complexity or because of their individual experiences with cases like it. This one involved a 70 year old woman with symptoms of aortic stenosis, moderate mitral stenosis, and lung damage. The choice to proceed hinged on what they needed to do first, and how effective that first surgery would be in remedying the other issues. It was a quiet, well-mannered battle of aortic vs. mitral repair. One doctor chimed in to say that non-surgical procedures are what they really need to think about, because the risk is just too high to immediately consider surgery. After a lengthy discussion, I recall that they decided it was an inoperable situation; they would do the best to make the woman comfortable, but going through surgery would just be a waste of her remaining time. Being realistic is a key part of making these calls, but listening to these conversations is sobering in a world of advanced medicine. Not everyone can be saved, and the outcome won't always be great or optimal, but that's life.

That's about all I have for this week. The storyboard for the aortic stenosis project is in its second draft, and since this post is so long, I'll shorten details for the coming Friday's post and put some info/photos of it there. Whether you made it all the way through or not, thanks for reading!

Thursday, February 25, 2016

2/24/16

Today I decided to come in to watch one of Dr. Nguyen's cases, a mini-mitral valve replacement. I didn't have any background knowledge about the patient, but being there was interesting enough; this was the first mini I've seen, and also the first operation I had seen performed on the mitral valve. The mitral valve is the first valve to be reached by oxygenated blood coming from the lungs, and is located between the left atrium and the left ventricle. A mini is a minimally-invasive surgery, which relies on 1-4 incisions around the thorax to perform the operation, as opposed to a sternotomy that splits the chest open entirely. Although there are many factors to consider, some people just don't like the recovery time involved with a sternotomy, and might pick a mini operation over it if given the choice.

The surgery starts with an incision in the lower left of the chest, near the groin; this leads directly into the femoral vein. A cannula (fancy word for tube) is inserted into the vein, and is connected to a heart-lung machine. Another cannula is drawn from the heart-lung machine to the femoral artery, creating a system that draws out blood, reoxygenates it outside of the patient, and feeds it back into the lower body. Another incision is made on the right side of the chest, just under the breast, and the hole is widened with rib spreaders. With his incision opens up a view of the pericardium, the area surrounding and holding the heart, from the ascending aorta to the diaphragm in length. The pericardium is then cut open, and sutured in place to reveal the aorta. Cardioplegia is administered- which slows and eventually stops the heart- so that the journey to the mitral valve can begin. This process is quite extensive( and definitely looks the part), as the doctor has to get all the way to the mitral valve from a hole in the pericardium. It really ends up looking like a tunnel, and gets even more confusing once the sutures and ties holding tissue in place are set. The sutures divide the tissue layers, allowing a small hole of viewing space into the mitral valve. Because of how tightly-packed the area was with sutures, clamps and cannulas, it was satisfying to be able to identify the chordae tendonae peeking out from behind the relaxed mitral valve. It was sort of like a medical version of "Where's Waldo."It was around this point that I realized that Dr. Nguyen was doing a full valve replacement. He started clipping away at the mitral valve's leaflets, and removed the valve surprisingly quickly. The replacement valve was to be mechanical, so he began attaching the sutures to the lip lining the mechanical valve, a part of one of the most complicated processes I've seen in the OR- I'm talking about the scaffolding/lowering-of-the-replacement-valve process, which secures the new valve in place. The ends of those sutures attached I wasn't able to stay to see the heart tissues sutured back together, which is a bummer, but I'm glad that I got to see most of the installation process. Because the patient received a mechanical valve, they will have to take Coumadin or Warfarin (blood thinners) daily for the rest of their lives; the structure of the mechanical valve allows blood clots to develop more easily, so this is a safety precaution.

Having seen both kinds of surgery, sternotomies and minis, sternotomies are much more appealing from the viewer's perspective. One would assume that it's easier on the doctors, too- the chest is split, and there's plenty of viewing room. It's a direct look at the heart, and all of the doctors surrounding the patient can see what is going on. Minis, on the other hand, are performed through the right of the chest, and docs assisting with the surgery have to rely on the performing doctor's live headcam footage to get a peek. I would've had no idea what was going on without Dr. Nguyen's headcam footage being projected on the nearby flatscreen TV. Even the surgical instruments involved in it are long, complicated and awkward; the highly trained professionals involved with this surgery struggled, at times, to position cannulas and other materials around the chest incision.

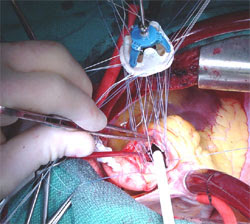

Above is a clean picture of the surgery, with clamps, cannulas, sutures and the rib spreader in place. This is still pre-valve installation

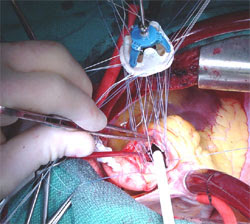

Above is a real picture (not mine) of the suture scaffolding, lowering the replacement valve in.

I thought that this deserved a long blog post, because seeing actual surgery is one of the most interesting things about this internship. The human body is incredible, and what we're able to do with it in regards to medical care is even more astonishing. Hopefully I'll be able to spectate one surgery every month or so, but because they're so long and right in the middle of the day, planning gets a bit tricky.. I'll have another post about this Friday's events (as promised) up by the end of the weekend.

The surgery starts with an incision in the lower left of the chest, near the groin; this leads directly into the femoral vein. A cannula (fancy word for tube) is inserted into the vein, and is connected to a heart-lung machine. Another cannula is drawn from the heart-lung machine to the femoral artery, creating a system that draws out blood, reoxygenates it outside of the patient, and feeds it back into the lower body. Another incision is made on the right side of the chest, just under the breast, and the hole is widened with rib spreaders. With his incision opens up a view of the pericardium, the area surrounding and holding the heart, from the ascending aorta to the diaphragm in length. The pericardium is then cut open, and sutured in place to reveal the aorta. Cardioplegia is administered- which slows and eventually stops the heart- so that the journey to the mitral valve can begin. This process is quite extensive( and definitely looks the part), as the doctor has to get all the way to the mitral valve from a hole in the pericardium. It really ends up looking like a tunnel, and gets even more confusing once the sutures and ties holding tissue in place are set. The sutures divide the tissue layers, allowing a small hole of viewing space into the mitral valve. Because of how tightly-packed the area was with sutures, clamps and cannulas, it was satisfying to be able to identify the chordae tendonae peeking out from behind the relaxed mitral valve. It was sort of like a medical version of "Where's Waldo."It was around this point that I realized that Dr. Nguyen was doing a full valve replacement. He started clipping away at the mitral valve's leaflets, and removed the valve surprisingly quickly. The replacement valve was to be mechanical, so he began attaching the sutures to the lip lining the mechanical valve, a part of one of the most complicated processes I've seen in the OR- I'm talking about the scaffolding/lowering-of-the-replacement-valve process, which secures the new valve in place. The ends of those sutures attached I wasn't able to stay to see the heart tissues sutured back together, which is a bummer, but I'm glad that I got to see most of the installation process. Because the patient received a mechanical valve, they will have to take Coumadin or Warfarin (blood thinners) daily for the rest of their lives; the structure of the mechanical valve allows blood clots to develop more easily, so this is a safety precaution.

Having seen both kinds of surgery, sternotomies and minis, sternotomies are much more appealing from the viewer's perspective. One would assume that it's easier on the doctors, too- the chest is split, and there's plenty of viewing room. It's a direct look at the heart, and all of the doctors surrounding the patient can see what is going on. Minis, on the other hand, are performed through the right of the chest, and docs assisting with the surgery have to rely on the performing doctor's live headcam footage to get a peek. I would've had no idea what was going on without Dr. Nguyen's headcam footage being projected on the nearby flatscreen TV. Even the surgical instruments involved in it are long, complicated and awkward; the highly trained professionals involved with this surgery struggled, at times, to position cannulas and other materials around the chest incision.

Above is a clean picture of the surgery, with clamps, cannulas, sutures and the rib spreader in place. This is still pre-valve installation

Above is a real picture (not mine) of the suture scaffolding, lowering the replacement valve in.

I thought that this deserved a long blog post, because seeing actual surgery is one of the most interesting things about this internship. The human body is incredible, and what we're able to do with it in regards to medical care is even more astonishing. Hopefully I'll be able to spectate one surgery every month or so, but because they're so long and right in the middle of the day, planning gets a bit tricky.. I'll have another post about this Friday's events (as promised) up by the end of the weekend.

Saturday, February 20, 2016

Update 2/19/16

Dr. Nguyen was unavailable on Friday- so, I'll probably be going early in the week. Progress is still being made on the storyboards for the animation project, and I will likely be uploading full rough draft pictures in the coming posts. I could very well be doubling up on hospital visitation next week, as I have to make up for this Friday and will be going-as per usual-next Friday morning. I'm hoping to spectate a surgery for the makeup day and have a normal morning for next Friday (valve conference, maybe a lecture, patient visits, and project updates), but that all depends on Dr. Nguyen's schedule. It'll be an interesting week regardless, so stay tuned.

Monday, February 15, 2016

2/12/15

Today was the most radical departure from my normal Friday schedule. Dr. Nguyen was busy in the morning, so I went at three in the afternoon instead. My main goal of the day was to present to him some work that I'd been doing on an animation project, but some patient drama arose just as I got there; this resulted in him rushing over to the Heart and Vascular Clinic across the street, with me in tow, to make sure that a patient's temporary pacemaker got installed. That aside, the project that I'm working on is intended to explain medical conditions in simple terms, so that a layman audience can understand what's going on. There's an entire set of jargon in medicine, and it can be quite challenging for many people to keep track of it all. I'm using aortic stenosis (the tightening of the aortic valve) as a start, developing a short story around it, and tying in an explanation of the disease. I'll probably post some images of the work, especially once we get it past the storyboarding process, but I thought this would be a good entry- as opposed to the standard blog post about some surgery or disease I just learned about.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)